For years, I wanted to write a short story in the vein of Robert Lawson’s Rabbit Hill, but with a Fielding theme and a Dickensian vibe. It was one of those projects I thought would remain a wish—an ambition to stimulate my mind on long car trips and sleepless nights, but would never come to pass. But then, last Christmas, opportunity knocked. I would not go so far as to describe what occurred over Christmas of 2024 as a stroke of luck—in fact, it created quite the calamity—but it provided me with all the inspiration I needed to craft my ambitious little tale. The modest work has been tucked away on my “essays” page since last New Year, and I thought, because it has a Christmas theme, mid-December would be a good time to dust it off. I couldn’t say whether I hit the mark or underdelivered, but, nevertheless, here it is, my humble Christmas offering:

A Requiem for Oliver Clinch

By

Michael DeStefano

Not all elegies echo for the dearly departed. Some canticles of pathos ring for an unceremonious eviction.

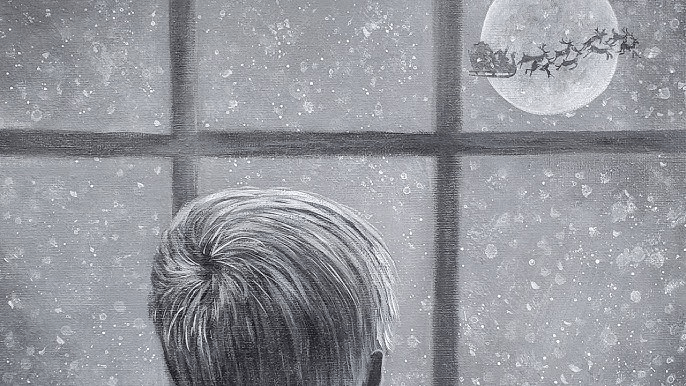

It was a cold winter’s night, the twenty-fourth of December. A solitary soul roams the quiet lanes of a village during a time of anticipatory slumber. The lights in the village shops had dimmed; only the streetlamps were aglow, and nary a soul was afoot. Snow thickly dusted what hours ago were sidewalks that accommodated last-minute shoppers in search of a final treasure. The snow’s glittery descent glimmered in the streetlamps and the full wintery moon—a crystalline delight characterized this sleepy hamlet in repose.

Oliver Clinch had been walking for hours. The throng of merry bustlers had largely ignored him, though some took a moment, however briefly, to engage him with an enthusiastic nod or cheery grin—a child, in a momentary gush of glee, had pointed in his direction. Come dusk, the air grew frostier. With gloved hands, many pulled collars snug to their necks and hastened their strides, sparing no thought for Oliver Clinch.

And then darkness fell. The swarm of merriment thinned to a smattering of shiverers anxious for their next destination. The shopkeepers turned their signs to closed and ambled toward the village church. Oliver Clinch stood alone, his tiny nostrils pulsing in the cold.

Before long, there was no one about but Oliver Clinch. And thus, he ambled about the town alone in the frigid night air. Through one window, he watched men clanking mugs of ale, their toast a crescendo of jollity; through another, a woman prayed to an infant, many years ago born a king. On he went, up one lane and down another, imagining the balmy days of summer. The clock struck midnight; its gong had echoed that it was Christmas Day. But for whom was it Christmas? Using a bare extremity, a thirsty Oliver Clinch drew a dollop of snow to his mouth.

And then the night grew colder yet; it took no pity on Oliver Clinch. The midnight mass ended; its chorus of hallelujahs echoed into silence, swallowed by the icy air. At the base of a stone wall, away from the wuthering wind that stung his eyes, Oliver Clinch had crouched. He tilted his head skyward and cried, “Please. Please, Sir. I’ve done my very best.”

No sooner had his words of desperate entreaty echoed and died than he spotted a cellar casement just yonder, did Oliver Clinch. He scurried across the way, peered through the pane, and prayed, “It’s Christmas, Sir. Have mercy.” Next, he gave the casement a push, and it budged! He pushed again until it opened enough so that he could gain passage to the other side. Then, in he went, careful not to make a sound. Next, he crouched in a corner obscured by a heap of odds and ends that typically accumulate in cellars. He sighed, did Oliver Clinch, that he had escaped the harshest of winter nights. As the warmer air settled in his lungs, his lids grew heavy and then heavier. Before long, he drifted off into a peaceful slumber, setting aside the fear of someone discovering that he had trespassed.

Morning came. Church bells rang. It was Christmas in the village.

Oliver Clinch woke to the footfalls of someone descending a staircase. He stiffened. Next, he heard them overhead. Before long, an aroma roused his olfactory senses. It was strangely familiar; he had experienced it once before in a time of yore. He recalled Absolom James telling Mortimer Grumby, “I know what ‘that‘ is; it’s what ‘they’ drink.”

“They?” intoned Mortimer Grumby.

“Indeed,” replied Absolom James. “And if ‘they’ drink it, then it must be terrible.”

Before long, others joined the one in charge of brewing the aromatic potion. The scene became a clamor filled with shouts of Merry Christmas, Cornelius, Cynthia, Mummy, and Father, joyfully ringing. Next, the aroma of blueberry muffins trailed through the house; it had accompanied the ripping of paper and the “oohs” and “aahs” that are often expressed when one receives an item they have long coveted.

“Whatever could it all mean?” Oliver Clinch muttered to himself while crouched in the cellar.

“It’s what I always wanted,” cried Cornelius.

“How could he have known,” chanted Cynthia as she unveiled a treasure thought delivered by a Ukrainian Saint.

Oliver Clinch nearly succumbed to curiosity but dared not ascend the stairs. Next rang the glorious tune Hark the Herald Angels Sing.

“Oh, that again,” Absolom James had long ago bemoaned.

“They sing it yearly,” Mortimer Grumby had sourly reminded his friends.

And thus, Father, Mother, Cornelius, and Cynthia set out to the village church.

“Look, Mummy,” cried Cynthia as she twirled about on the sidewalk, “It snowed last night!”

“From Christmas Eve into Christmas morning, it did,” cried Cornelius.

“It seems,” Father began, arching an accusatory brow, “that someone was spying from their bedroom window looking for ‘you know who’ when they were supposed to be sleeping.”

“Not I, Father,” Cornelius swore. “I was asleep the whole time.”

Meanwhile, Oliver Clinch crept up the cellar stairs and inched open the cellar door. He knew the coast was clear; still, he tiptoed into the kitchen. An empty muffin pan sat atop a table. Beside the pan stood a basket lined with linen. Four muffins were missing, and eight had remained.

“They’ll never know,” said Oliver Clinch, and he snatched one of the muffins, promptly devoured it, every crumb, and made haste for the cellar. It seemed that he had scarcely settled in his familiar corner when all four Crows, Father, Mother, Cornelius, and Cynthis, returned from the village church.

“Cornelius, did you help yourself to another muffin?”

“No, Mummy,” Cornelius swore. “If one is missing, it was not I who ate it.”

“Cynthia?”

“No, Mummy. My tummy is too small to have eaten a second.” Pointing, Cynthia drew everyone’s eyes to the tummy deemed too small to accommodate a second muffin.

Father made for the cellar. “I’m going to fetch some wood to make a fire,” he said.

The sound of plodding footfalls on the cellar stairs terrified Oliver Clinch; he crouched lower, moving nary a muscle, and held his breath.

“Hmm,” intoned Father. “That’s odd.” When he returned to the kitchen, with a log tucked under each arm, he said, paradoxically, “Funny thing, one of the cellar windows was left ajar.” He looked first at Cornelius, who swore, “I didn’t open the window, Father,” and then at Cynthia, who peeped, “Father, surely you can see I’m much too tiny to reach the window.”

Oliver Clinch shuddered, thinking that his presence and actions sent the household into an upheaval. He recalled once when the very wise Absolom James explained to Mortimer Grumby, “They account for all matters big and small, they do. There is no such thing as a matter so inconsequential that it could not provoke a war. Even more bizarre, it was they who coined the axiom Let bygones be bygones. Oh, the irony!”

Before long, the household became a potpourri of aromas and a menagerie of clatter. The Crows and their relations sang, danced, ate, dipped into a punch bowl (some more liberally than others), and lauded a babe born many years ago into a fraught world. And just like that, it was over. Despite all the anticipation, preparation, and commotion, the calendar, by way of its usual increment, lurched forward. And there, alone, in a darkened cellar, his back to a clammy wall, crouched Oliver Clinch. Absolom James and Mortimer Grumby must be sick with worry, he sadly imagined. I shall have a devil of a time explaining what happened. He glanced up at the casement Father had shut and locked. Unlike Cynthia, he could climb to reach it, but he lacked the strength to unlock it. Alas, a place of refuge from a harsh winter night had proved a trap. But wait! The Crows were all nestled in their beds, fast asleep. He had many rooms to explore, did Oliver Clinch, and thus, he went tiptoeing up the cellar stairs.

Come morning, before Father brewed his aromatic potion, he exclaimed, “What on earth…?” Mother dashed to the top of the stairs and cried out, “What is it, dear? What’s wrong?”

Before long, all four Crows, Cornelius, Cynthia, Father, and Mother, were present in the kitchen.

“Can anyone explain this?” Father demanded to know, his mien twisting with vexation as he pointed to a banana peel left to rot beside the stove. Incredulity registered on the faces of Mother and Cynthia. Cornelius frowned with dismay.

“And what of that?” Father had alluded to pieces of tangerine rind littered atop a windowsill. His demand for knowledge was met with similar looks of incredulity and dismay. “I would say,” he grandly proclaimed, “we have a hungry intruder in our midst. What say you, Mum?”

Mother’s shrug suggested that she concurred. The notion of an intruder, hungry or otherwise, frightened Cynthia.

“What do you plan to do, Father?” The concern that manifested in Cornelius, although palpable, was somewhat ambiguous. Was it the hungry interloper he feared or what Father planned to do to one so bold?

Father grabbed the iron he used for poking the fire. “I’m going to the cellar,” he said, scowling. “I’ll bet that’s where the brazen rascal is hiding.” Oliver Clinch shuddered, knowing he had to find a way to escape or face the gravest of consequences. Father went charging down the cellar stairs, waving his poker and yelling, “I’ll thrash you, I will!” Before long, he cried, “Ah-ha, you rascal, it’s time for you to go! We don’t tolerate your kind in our village!”

“Oh, please, Sir,” peeped Oliver Clinch. “It was dark and cold, and the wind was wuthering. And, besides, it was Christmas.”

Oliver Clinch raced up the cellar stairs. Father followed, waving his poker. Cynthia stood agape at the intruder’s swiftness, and Mother shrieked.

“Father, don’t!” cried Cornelius. “He-he’s my…” Cornelius held his tongue. Then he dashed to the kitchen door, flung it open, and out went Oliver Clinch.

“He’s your what?” Father menacingly intoned. Cornelius could not answer. Moreover, he hung his head in despair. Later that day, Absolom James bellowed, “For crying out loud, Oliver Clinch, where have you been? Mortimer Grumby and I have been sick with worry.”

“I’m awfully sorry, Absolom James and Mortimer Grumby,” said Oliver Clinch, his tenor genuinely regretful. “It was never my intention to cause either of you distress. Truly, it wasn’t.” Next, Oliver Clinch explained, “I’m sure you both remember, for I mentioned it often, how I wanted to see the village on Christmas Eve. It was all quite festive, with strings of lights and folks calling Merry Christmas. But then it grew dark and did so faster than I realized. And you need no reminding how poor my sense of direction is, even in daylight; I was terrified I wouldn’t find my way home. And those keepers lock the village shops up tighter than drums they do. Still, I feel compelled to mention that they’re not all bad. Most are bestial, naturally; evolution doesn’t work that quickly. But there are a rare few who do seem to grasp the concept of love and compassion.”

“Hard to imagine,” said Absolom James.

“Indeed,” added Mortimer Grumby.

Oh, have I got a story to tell,” Oliver Clinch brightly intoned.

Over in the village, Father asked Mother and Cynthia, “Where’s Cornelius? I haven’t seen hide or hair of him all day.”

“He seems to have banished himself to his bedroom,” said Mother.

“He brought along a tablet and pen,” Cynthia thought to remark.

… and then the boy stirred when the night was darkest, and everyone was fast asleep. He had a premonition of a desperate soul in need; perhaps they were cold and hungry. He lit a candle and crept his way to the cellar.

“Shhh,” said the boy with a finger to his lips. “You have nothing to fear.” Then, the boy disappeared briefly and returned with a crust of bread. “Here,” he said. As the boy watched the hungry soul nibble the morsel, he thought aloud, “I shall call you Oliver. Oliver Clinch. Would you like that?”

Oliver Clinch seemed pleased with the name the boy had chosen.

I believe you and I shall become fine friends, Oliver Clinch, very special friends indeed.

Next, the boy told his new friend that he could expect a blueberry muffin come morning.

“Good night, Oliver Clinch. And Merry Christmas.”

“So, I guess there’s hope for them after all,” Absolom James and Mortimer Grumby reluctantly conceded.

“If only they could remain as children,” said Oliver Clinch.

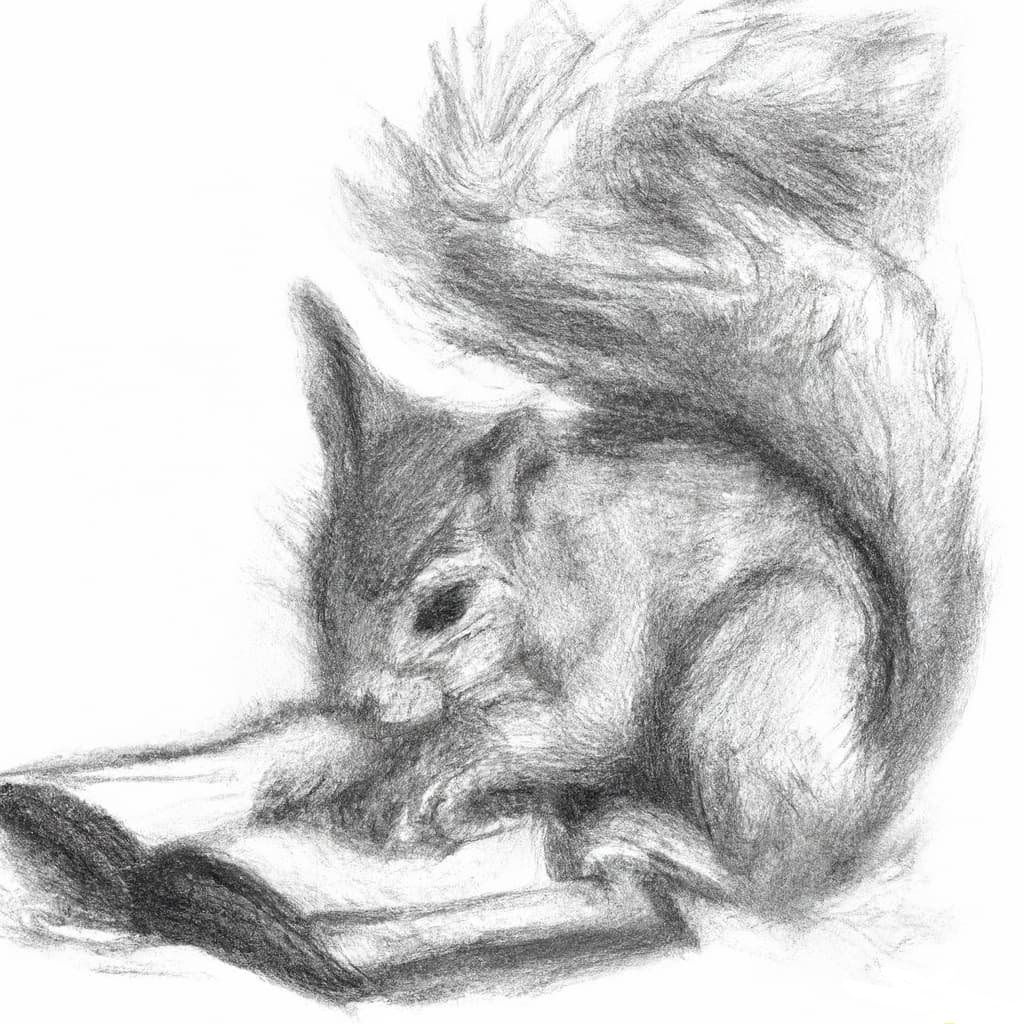

A Portrait of Oliver Clinch

Leave a comment