The Boy Who Walked with God

By

Michael DeStefano

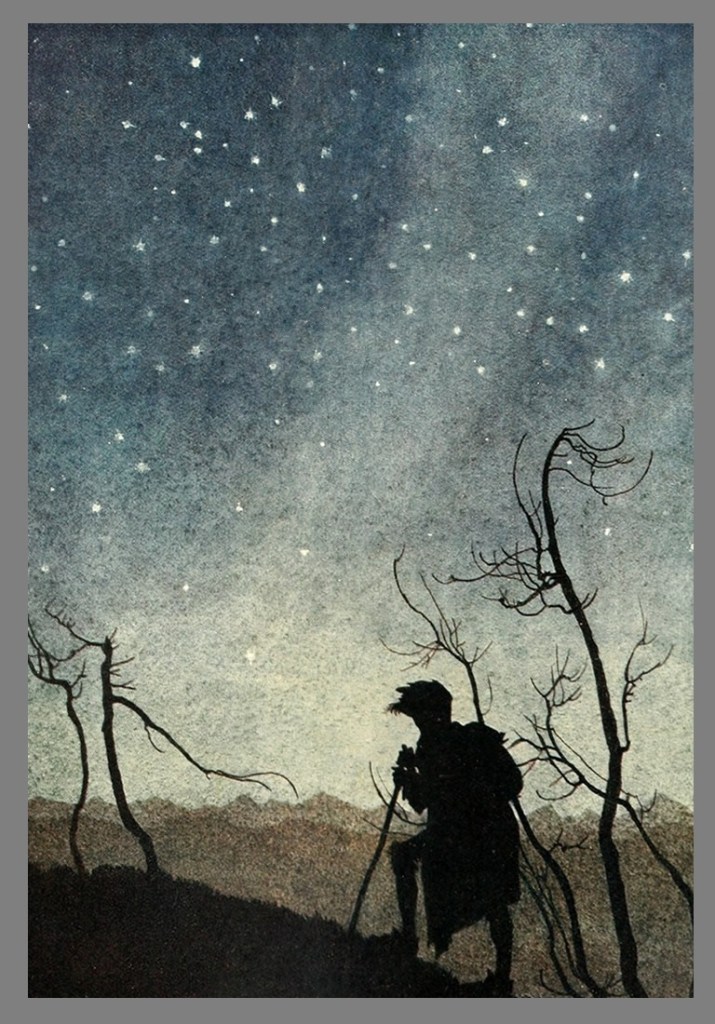

Let This Be My Last Pilgrimage

And the Bell Tolled for the World’s Lost Children

Love is fleeting. Death is eternal. Or is it the inverse? It is but one dilemma foreshadowing a boy. Another is that he is God’s instrument, wielding the power to reshape the lives of those he cherishes. Each pursues with equal vigor.

BOOK I

A WAYFARER’S PURGATORY

At a time commonly referred to as the crack of dawn, a boy, perhaps age fifteen, settles a door into place without a sound and sets his feet upon the road. He will carry in his heart the weight of an ultimate act. We shall call the boy Andy.

Swiftly, Andy ambles through the dark dawn of a sleepy hamlet until he reaches the cornfield, a place of idyll where he and Karen would lie in a row, the tops of their head touching and conducting the vibrations of each utterance. They spoke of discovery, philosophy, friendships, and a shadowy time called the future. Unmentioned during these periods of teenage idyll is the depth of depravity an adoptive sister endures. The reality would prove too startling for a boy in the autumn of youth. Or would it?

Before long, he arrives at the railroad tracks on the outskirts of town. He turns eastward. Why? He is far nearer to the Atlantic than the Pacific and has never seen an ocean.

Mile after mile, Andy trudges—a solitary youth alongside a railroad track. It leads to a wood where a growling tummy harmonizes with chirps and other woodland echoes. He veers from the tracks to a road and trusts Highway 308, and a sign that reads Welcome to Clintonville would prove a gateway to filling the hole in his belly.

Name a country in any hemisphere, and Andy could rattle off a town or ten, yet Clintonville—a town a mere county over, unlike the far-flung places he hoped to explore—was foreign. He took in the countryside and saw what one would expect: scenery that rambled until it reached the horizon. He swallowed feelings of momentary gloom and recalled the rules for itinerant orphans: You are not lost if you never knew where you were in the first place. Fear no journey. There is no point in fearing the unknown when you know nothing. Equilibrium is as close as your next step.

Down the road, Andy came upon a repair shop, a ramshackle old hut. He found it curious that a place meant to fix things appeared in disrepair. He peeked through a filmy pane and saw car parts scattered on the floor. The sound of metal striking metal echoed outside the shop. Andy followed the sound; it led him down a chip stone driveway, where a tractor stood. Bent at the waist, with his head hovering over the engine, was an old man. His wavy white hair and ungroomed beard of equal whiteness were features that first struck Andy. Next noticed was a narrow, intense gaze. Andy approached with mild trepidation. The oldster continued tinkering. Andy watched with a measure of curiosity before calling, “Sir?” He lingered longer than it should have taken for the oldster to unbend his waist and acknowledge another presence afoot. Andy kicked gravel and cleared his throat as one might after swallowing a gnat, then settled on the notion that a man who restored old tractors for a Saturday hobby was willfully ignorant or hard of hearing.

Finally, the old man turned his gaze upon Andy. The demeanor with which he uncoiled and faced his visitor gave Andy the impression the oldster was aware of his presence all along. Resisting a grimace, Andy called, “Good afternoon, Sir. Or is it still morning?”

The old man tugged on his sleeve, revealing a wristwatch band stretched to where it required the meatier part of his forearm. “Says here, it’s still mornin’.” It was apparent in the man’s expression that he was unbothered by an unexpected intrusion and grateful for an opportunity to unbend his waist and relax his gaze. “What can this old man do for a young fella on a Saturday mornin’?”

“I’ve been on the road for a spell and could use a bite. If you wouldn’t mind steering me in the right direction….”

The old man took a handkerchief from his shirt pocket and patted his brow. He peered over Andy’s shoulder at the road where he expected to see a vehicle and said, “I was about to break for a bite myself. Got plenty of leftover chili inside.” He gestured toward his shop. “You’re welcome to half. The missus sends me with enough for an army. You know how it is.” Assessing Andy, he chortled and said, “I take that back.”

Andy winced when imagining food that sat for a day in a ramshackle hut that served as a repair shop. He envisioned a plate sitting atop a well-stained countertop next to an oily rag that served as a napkin and a spoon with the hardened remnants of the first go-around. After taking in Andy’s twisted expression, the man offered the concession, “I guess cold, day-old chili doesn’t sound appetizing.” He cleared his throat and said, “A bite to eat; I didn’t forget,” then directed his unexpected visitor to Butler Road. “A mile and then a left. They call the place The Way-Out Diner. She’s not much to look at, but she’ll fill that hole in your belly.”

Andy glanced over his shoulder at a garage that appeared a gust away from a pile of rubble, then grinned that the oldster had assessed an eatery as unappealing. As he turned to leave, the man said, “I have a good feeling about you, Son. You’re gonna make it.”

The man’s words echoed curiously. Of course, Andy would make it; he had but a mile to walk. Or had the man implied something else? Andy turned to ask, but the oldster had his back to him, his head buried in an engine, and thus went his ability to hear.

*****

What transpired between Andy and the oldster was hardly the launch of a relationship, but it made the road seem less daunting. Still, the man’s parting words haunted Andy.

As Andy would soon discover, there was nothing faulty with the oldster’s eyesight: The Way-Out Diner was an eyesore. Foremost, it lacked accord with the road, which meant the road was subsequent or the builder unpardonably careless. Another theory was that some folks have quirky ideas concerning how things should appear. This rural monstrosity, which may have had a coat of paint applied to it after falling to Earth and landing askew, became novel for its appearance and would remain so, assuming it doesn’t go up in flames: it was a fire hazard, ignoring every known code, which wasn’t rare for establishments situated in areas some call the middle of nowhere. But how does the maxim go: Don’t judge a book by its cover? Legend has it the establishment earned its name when Claire Haskins bellowed to her husband, “Harley, what are you doin’ building a diner way out there?”

Boisterous men sporting unkempt beards with rifles slung over their shoulders came spilling from the diner; they were reminders that Andy was a boy in a man’s world, a rough man’s world with little tolerance for an interposing youth. With an ear to the door, Andy listened to a diner brimming with local commotion. Dismayed, he reached for his bare chin and prayed he wouldn’t be the only one not brandishing a mechanism capable of stopping a charging full-grown mammal. Suddenly, cold, day-old chili didn’t sound unappetizing.

Strangers in strange places imagine they are magnets for every set of eyes. Andy was tall and lean and had a long chin and ears that one might describe as generous. He did no favors to his gangly composite by how unnaturally erect he stood. Moreover, since he was trapped in the throes of an outlier’s deportment, he failed to notice the only soul in the establishment that qualified as a peer until upon him. She broke his gaze into open space with a hand on his elbow. Her tacit greeting was a smile that chased Andy’s trepidation; it seeped from his pores, and his shoulders slumped. She escorted him to a table suitable for a lone diner, then handed him a sticky, well-smudged, wood-burned menu.

“Kinda historic when ya think about it,” she said when observing the gingerly manner Andy handled the dirty wooden board darkened from age. “Some important folks have dined with us; there’s no tellin’ whose prints are on the wood. If you’re wondering about the specials, there’s none this weekend; it’s just whatcha see on the board.”

“What’s Dante’s Inferno?”

“It’s what folks around these parts call chili. But how would you know? You aren’t from around here. But doncha worry none, soldier; I won’t hold it against you.” Next came a wink. Andy struggled to imagine what he had in common with a girl who referred to her hometown as “parts.”

“I’ll have the number five.”

“The whoop-ass double-decker beef?”

“Yeah, that one.”

“Too much a gentleman to call it by name? That’s okay, soldier; I won’t hold that against you, neither. Hope you like horseradish. A beer with that?”

“Milk.”

“You’re joking, right?” Meeting Andy’s gaze, she said, “Why, you’re just full of surprises, are n’tcha, soldier?”

Country pretty with a siren’s eyes would best describe her. A torturer of men would be another. Yet she ambled about insensibly to what Andy alleged was clear and present danger—men as tough as the coal, steel, and timber from which they earned their livings—or it was she who was the wielder of peril. Andy was nearing the end of his number five and milk in a mason jar when the siren reappeared. Her wispy blonde locks hung in loose tendrils against her neck and cheeks; she wore her blouse untucked and bowtied above a flat, creamy midriff; her blue jeans were a second skin, announcing with emphasis her below-the-waist assets of which everyone took appreciative notice. She stopped and planted herself alongside Andy’s table and struck a pose that saw her place a delicate hand on the table’s well-marked wood, balance her person utilizing a boot-clad foot no bigger than a child’s, and curl her free leg around the plant one. She maintained this precarious carriage with the grace of a ballerina. Before long, she swayed as though she might fall into Andy’s lap. What saved her was whipping the hand she had tucked behind her back onto the table. Invading Andy’s space, she uttered the breathy words, “Where ya from, soldier?”

Andy guessed “soldier” was a term the girl used on unfamiliar young men when her objective was for them to become less unfamiliar.

“A bit west of here.”

“I see you’re readin’ Huck Finn.” Her eyes shifted down to where the book rested. “Folks around here aren’t much for readin’, not unless it’s magazines on fishin’, huntin’ an’, taxidermy.”

“I read it this past winter.” He saw no sense in passing judgment on the latter.

“Then why are you carrying it around?” Aggressively, she took hold of it. After peeking inside the cover, her eyes flared. Indicative of an adversarial tone used by a girl whose trust got mishandled, she asked, “Who’s Karen?”

“Someone I used to know.” Suddenly, cheeks that had flushed from female incursion drained into sadness.

“Everyone’s gotta past. But that don’t mean ya gotta stay stuck in it. Besides, the future’s more exciting. And while we’re on the subject, where ya headed, soldier?” She followed what she hoped would prove a restorative question, adding, “Not home so soon, I hope. This town can be a nice place to visit if ya catch my drift.”

Andy’s mouth turned to dust. For one so petite, it was alarming how imposing the girl made herself; she was far more in consonance with the psychology of womanhood and its potency than Andy was with manhood.

“East, to visit relatives,” came his alert fabrication despite the thread of the conversation fraying in his mind.

“Must be nice to have relatives.” The girl was not soliciting sympathy but giving Andy a subtle gradation to presume her situation. “Incidentally, soldier, I checked the calendar this morning, and I saw nothing tellin’ me it was a holiday, so I’ll bet those relatives of yours won’t mind waitin’ on ya for a spell.”

She was not proud. There were aspects of feminine mystery she could ill afford.

Andy searched the wall for a clock as though no issue was more paramount than time. “I should get going,” he feebly uttered. Keeping to the notion he was not a lost cause, the girl intoned, “What a shame. ‘Cause it’s a funny thing, opportunity; it doesn’t knock when convenient, and most generally, we get only one bite at the apple. But…” She paused and sighed to emote resignation, “…I’m a girl with a heck of an intuition for folks, and I’m bettin’ you’re the type that would rather do something every day to make his mama proud than sweepin’ a girl off her feet.”

“That might be true had I a mother to make proud.”

“Looks like you and me are in the same boat, soldier. It may not be a cruise ship, but at least she’s afloat.”

Andy grimaced at the girl’s well-chosen allegory, then brightened that such a vessel would seem friendlier with another occupant.

“You be sure and stop in on your way back from those ‘relatives’ of yours.” Sliding her hands across the table to further crowd Andy, she whispered the breathy words, “By the way, the name’s Darlene. Just wanna make sure you know who to ask for when you return. Trust me, soldier, you and I will meet again.”

Darlene had no lasting memory of a mother; she was too young when the woman who bore her—a teenage runaway—made an unceremonious departure from the world. Raised by a man whose ambition to unload his daughter no sooner than she displayed signs of womanhood became the prevailing tenet that oriented this mid-teen siren. Darlene was thirteen when her father sent her to The Way-out Diner, where unsuitable men made crude overtures. Two years have come to pass. Every night, she returns home and is greeted with the same contemptuous sneer—like someone late paying rent—for failing to land a man willing to take her off her father’s hands.

Andy sputtered. Following an incoherent hodgepodge, he managed a word that bore a resemblance to his name.

“It was a pleasure to finally meet you.” He could taste Darlene’s breath; it was not unpleasant. “We’ve been waiting for you, Andy.” She pecked his cheek and disappeared. It was not until Darlene was out of sight that Andy became conscious that he had grown accustomed to the strain of her presence. Already, he felt lonely.

*****

When a matter is the degradation of a family, there is plenty of blame to share. The world is chock-full of perpetrators, agitators, victims, and deniers; everyone has a role to play. The characters are designated by the potent, assigned to the manipulated, and thrust upon the weak; it is rare to discover a bystander and even rarer to find one willing to act, sparing no thought for their wellbeing with an initiative to put matters right. But it can happen. It most definitely can.

Andy’s encounter with Darlene became a prevailing preoccupation; her voice stayed stuck in his head; he heard his abstractions and ruminations echoing back at him in her sultry intonations. Theorizing that Darlene was all façade—a lost soul obscuring a bleak reality using the tools available; an actress immersed in a role that had evolved into a perfunctory routine—a girl who relished the comfort of companionship sparked the desire to double back. But Darlene was miles away, and her parting words were no less haunting and incongruous than those of the tinkering old man.

Andy entered Moshannon State Forest, bounding between the spirit of adventure and the reality of a lost and solitary soul. Such peaks and valleys gushed upon him without warning, as did the dilemma of where he might lodge. And yet the parting words of a tinkering old man and waifish beauty continued to echo, as did his final encounter with Karen, not in their idyllic cornfield but in her darkened room at a desperate hour. All three were issued stern evictions but remained stubborn antagonists.

Hours had passed since the day began. Our wayfarer traversed a forest road walled in by countless tons of timber. How was it possible the Earth’s floor could support so much weight? How many trees have sprouted from the floor of a planet of many wonders? Was there one for every person who ever lived, or ten? The world would never run out of oxygen. How vast and incomprehensible was the physical world; if every tree were tossed into its oceans and sank, would sea levels rise… an inch? Pondering matters of wonder can make one feel fantastically insignificant—a transmigratory universal speck floating around infinity, owning a bearing and consequence too small to measure.

The Earth turned. The sun is at Andy’s back. Deer emerge from the forest in tandem. With grace and timidity, these gentle, majestic forest dwellers make their vigilant venture across the road, then bolt into the Moshannon’s southern tracts. Andy gives chase, but the denseness of the forest quickly camouflages their long, loping strides. Keeping to the trail, he spots picnic tables and benches; beyond these typical woodland accommodations, a pond. In the pond floated a rowboat; two patient men had their cast lines submerged. Andy used to watch men cast their lines in a local brook and wanted to give fishing a whirl. Karen reviled fishing; she considered it an act of human barbarism perpetrated upon creatures devoid of limbs to defend themselves. “How would you like to die from suffocation?” she once asked Andy.

The sun sparkled on the water’s surface; the arching branches of every tree encircling the pond received mirror-like replication, their reflections as perfect as stalactites in a cave pool. Andy kneels on the pond’s bank, submerges his hands, and draws water to splash on his face and moisten his hair. Before journeying on, he slumped at a picnic table. Using his index finger, he traces a heart carved on one of the planks that help make up the tabletop. In it is the inscription Gary and Jen ‘73. Directly across are Mickey and Louise ‘69; their names required a larger heart. At the other end was the claim Zack was here ‘63. Zack hadn’t a lover to carve into a heart; perhaps he was but a youth. Whether accommodating soul mates or souls still searching, the picnic table marked history: From Kennedy’s assassination to Apollo 11 to the Paris Accords—a turbulent decade. The table hosted two more pairs of lovers; the year was 1969: George and Pat, and Becky and Lee fell in love in a year marked by Woodstock and the Amazin’ Mets. Years attached to events that shaped the times were all represented—good and bad. Andy searches the area for a sharp stone. When he is through toiling, he takes a moment to admire his handy work: An unknown traveler, ‘77—the year President Carter pardoned evaders of the Vietnam War.

The sun hung low; it would soon disappear. Fifty minutes span the sun’s vanishing, the moon’s arrival, and a night sky edging toward the peak of darkness. Strange, the matters one must consider when deprived of accommodations, friendless, and a wayfarer. Days ago—three, to be precise—Andy listened to cheers cascading from the stands as he all but lapped another field of milers. Karen sat among the captivated attendees, beaming with pride over his performance. Andy could always decipher Karen’s cheers echoing from the crowd.

From adulation to an itinerant tramp: the fall was too far, precipitous, and novel to rationalize—his journey too young to embrace or advocate a palpable goal—still, he clung to the notion all souls are hardwired to a force both grand and omnipotent.

Andy purported to have seen enough trees for a lifetime. Moreover, with dusk shadowing the land and poised to introduce darkness swifter than he would have preferred, he prayed the forest would end sooner than later, for a tunnel formed by trees could prove daunting in the dimness of night and rouse his worst thoughts to prevail. He craved open space, Earth’s expansiveness, and knowing that above hovered the wonder of empyrean and all its cosmic capacities. He imagined in a darkening vista the outline of a town, its dots of light—anything reminiscent that vital forces making up civilization occupied the finite world.

Indeed, darkness can prove a formidable foe and a tester of faith in the wilderness. But the Moshannon was not an endless wilderness that claimed its share of impulsive travelers. It ended. A lonely road that served as an unwavering companion became Highway 144. Still, the night wore on. Darkness, in its entirety, had set upon our wayfarer. There no longer prevailed a delineable vista to urge on an ill-vectored entity faltering, fraying, gritting with consternation, his skull walling in fear until fear became the only impetus. Anomalous questions and sentient thoughts bleed from his weary consciousness: Was today still today? Indeed, the Earth must have rotated more than once. All those Andy knew, past and present, became a collage of faces he failed to discern. Worse, they took no notice of him, this specter wandering a lonely road, gazing skyward toward the realm of empirical cosmology, hoping for divine mercy. Who are any of us at the core of existence but transmigratory souls traversing from vessel to vessel upon a pathway to infinity, or drops of water evaporated from an ocean to the ether, returned to Earth as rain to a brook, trickling to a stream, gushing to a river that returns us to the sea? There is too much blackness between the stars. How could the deific prevail among all that shadowy nothingness? Is it only to oblivion that the world’s lost children, the desperate and ill-oriented, may cling? Every step, every elapsed second, represents a curtain drawn on the past. To only have a future was a feeling both foreign and peculiar; it was equivalent to knowing only uncertainty or akin to knowing nothing. As Andy was discovering, doubt was a strange ally, but peace, by whatever means, must be made: One must convince oneself that an uncertain future is more promising than the past from which one fled.

Highway 144 turned into Sycamore Road. The wide-open spaces craved, now in abundance, did not send his spirits soaring as he had hoped. Before long, he uttered aloud, more for the company of a voice than confirmation concerning that which he suspected palpable, “Is that a light I see in the distance?” He was doubtful, even distrusting. But the light was not trickery to one whose weary mind had resigned to its conviction of eternal darkness; it was as real as Earth’s only satellite that stubbornly keeps its distance. The nearer Andy got to the light, the more he gained in equanimity, and should it prove a roadside eatery, he would be demonstratively appreciative.

The sign would have read The Snowshoe if not for the bulb behind the w burning out. Illuminated double-u or not, The Snowshoe was a known stopover for fishermen and snowmobilers of the Moshannon and others traveling east. Inside, the kind face of a forty-something woman greets Andy. Her name tag reads Regina. Her gentle tone possesses all the calm a weary traveler could hope to hear. Andy sags the way one might when fully submitting oneself to a person worthy of trust. Regina—a woman who ignored steely-gray locks that did not mix particularly well with the fawn-colored majority—in Andy’s judgment, was a bosom to a babe; one could allow themselves to fall backward and have every confidence in a safe landing.

“You look a bit road-weary, young fellow,” Regina remarks. “Been driving all day, have you?” Andy suffers a lapse in deportment. The untimely consequence is a burst of caustic laughter—ironic laughter contrary to humor. “I beg your pardon. Did I say something funny?” Regina maintains all the graciousness her job requires, though a discernible arch of a brow betrays what she thought of Andy’s laughter.

“My apologies,” Andy cried. “I passed road-weary hours ago and am working on punch-drunk.”

One might infer that passing road-weary hours ago meant Andy covered hundreds of miles and reached the center of Pennsylvania from another state—the western reaches of Ohio, if not Indiana. Regina assessed Andy as too green for a trip of such length.

“If that’s the case,” she proposes brightly, “we’ve got a meatloaf with mashed taters and gravy guaranteed to revive anyone.”

Andy sagged in his chair. With eyes floating in their sockets, he said, “Sounds like a slice of Heaven.” Regina smiled. It revealed a strange irony that left Andy feeling unsettled. Before Regina skipped off to the kitchen, she asked—it was a passing curiosity, not a concern— “What’s your destination?”

“I was told Lock Haven is a good town.”

“Lucky for you, you’re not more than twenty miles out.” Regina paused and warned, “Funny thing about destinations: sometimes you come upon them sooner than you realize. A young traveler would be wise to remember that.”

The Snowshoe drew locals, or what there was of a scant local population, but served mainly as a roadside stopover for travelers and adventure seekers of the Moshannon; many of the cars in the lot had camping equipment in tow. Andy scanned the sparsely attended dining area. Something struck him: The paradoxical look that came over Regina when he assigned the idiom a slice of Heaven to his dinner selection was apparent on the face of every diner. Moreover, the collective anomaly did not alter when a couple, well-seasoned, entered The Snowshoe. Wariness beset their aged faces, their bearing analogous to that of those who failed to imagine how they came to be at a particular place in time or dreaded why they were summoned. They sidled to a booth in the corner. Andy observed their effort. Next, a man, stout of form, abandoning a hand of solitaire, rose to his feet and began a resolute march toward the kitchen. As he neared his destination, his steps grew hesitant. He stopped, sighed, and then disappeared through the swinging doors.

“Who was that man?” Andy asked Regina.

“You must mean George,” Regina intoned. “He’s been dining with us for years. He had a friend with whom he used played chess, but the friend has long since moved on. Lately, George has resigned himself to solitaire.”

“Is he allowed in the kitchen?”

“No one can access the kitchen unless summoned by the cook,” Regina explains.

“I didn’t hear George’s name called.”

Regina places an assuaging hand on Andy’s cheek. “You weren’t listening,” she said before making her way to the old couple in the corner.

The farcicality Andy entertains begins to unsettle him. His day’s journey, the encounter in Karen’s room that marked its impetus: had it happened as he alleged, or was an increment of time, otherwise a day, a gross distortion of the truth, an existential catastrophe? Indeed, the notion of The Snowshoe as a waiting room where souls gather before being granted passage into a renowned place of idyll must qualify as absurd, as too is the notion he failed to survive the day’s journey.

Amid the smattering resonates familiarity; possibly, their deaths were a shared experience. Some seem too reconciled for their demises to have been recent affairs, and they have long since viewed death as a humorous irony, a way of escaping a fraught world. The concept of death is too novel for the couple in the corner; thus, they sit and fret. They are older; their lives require more review before passing the threshold dividing The Snowshoe and Paradise. They eye the swinging doors separating the kitchen and dining area with misgiving, for it is a gateway to the unknown. Andy shakes what he resolves are illusory and incoherent thoughts from his head and settles The Snowshoe as a place comprised of folks who, like him, are passing through, weary from the road and hoping food and a respite will revive them before continuing their journeys.

How far away was Darlene? The more time and distance separate Andy from a random girl who made a lasting impression, the more she manages to creep into his thoughts—the better he asserts to know her. The lost children of the world have a story. Andy had fabricated one for Darlene; thus, what passed as a brief and flirty encounter augmented to possess substance and meaning that otherwise may not have blossomed and whose measure had increased by the hour and mile. And there he sat, a stranger to everyone, a road-weary traveler longing for a familiar face, one owning the facility to revive him more than what he idiomatically called “A slice of heaven.”

The pleasing fabricated reverie of Darlene vanishes. What chased it away? Regina. Her reappearance jarred Andy, but the plate of food she brought was a welcome sight, one that cautioned our wayfarer that his lassitude was more significant than he realized. He would take his time with each morsel, then spend the night lying in the cool grass alongside Sycamore Road, his backpack for a pillow. And thus, the metamorphosis would see its completion: Andy as an animal, a survivor, a loner, who strayed from the pack, growing accustomed to living hour-to-hour, scavenging a forbidding landscape for whatever sanguinity it offered.

“Hope you saved room for dessert,” Regina chirped when she returned to check on Andy. “I’ve got a slice of pecan pie with your name on it.” That his name was assigned a designation, no matter how insignificant, drew a chuckle from our road-weary traveler. Whether his belly could accommodate it, pie and coffee entitled him to keep his seat.

When Regina returned, Andy asked, “Why am I the only one eating?” Regina replied, as though nothing could be plainer, “You’re the only one whose body still requires sustenance.”

“I don’t understand.” The wayfarer’s twisted expression pleaded for an explanation. As Regina sat and faced Andy, another rose to their feet, tossed aside a newspaper for which they seemed grateful to no longer feign interest, and began their plodding walk toward the kitchen.

“Is he going to see the cook?”

Regina nodded.

“Am I going to see the cook?”

“Not tonight, Andy. The cook no longer requires your presence. It’s rare, but sometimes we’re premature in our judgment. The cook has decided your work isn’t through.”

“Did I…” Andy dared not utter the word.

“Die?” Regina interjected. Then she smiled at Andy and asked, “Does it matter?”

“How did it happen?”

Paradoxically, Regina tells Andy, “Your pie is getting cold,” and walks away.

One by one, the locals and travelers awaiting their summons disappeared through the swinging doors to the kitchen. Only the elderly couple remained. With gratitude and trepidation, Andy exits The Snowshoe in favor of a cool night under a glittering country sky. Before long, the lights will dim in The Snowshoe, leaving only a gibbous moon and tiny points of light to shine down on our traveler. He prays that Regina, who intuited a troubled soul and thus showed kindness, won’t notice that he has made the roadside grass a lodging when she departs.

Prone to the Earth’s floor, Andy feels the world turn. A car approaches; its headlights pierce the dark. Regina places herself in the front passenger seat of a sedan that takes her away. Everyone belongs to someone except the lost children of the world; they are of a lesser god.

The events of recent days whirl in the head of one trapped in a wayfarer’s purgatory. He turns his gaze from the Heavens he prayed were beyond the empty blackness that accounted for the vastness of the universe to across the way, where still glowing were the comforting lights of The Snowshoe. His ears picked up the faint chugging of a freight train in the distance. The glow of lights, the chugging of a train: both were signs that, however fraught his existence or precariously he dangled, he endured a biospheric entity, a viable creature with capacities to effectuate, unequal bearing notwithstanding.

He imagined the glow from within The Snowshoe threw warmth and reconciled it was no coincidence a mile-long freight train chugged in the distance or that countless cicadas collaborated to render a symphony for a boy gone off the grid. But the coziness of such fanciful notions ended when the lights in The Snowshoe dimmed. The cook left the premises. Andy had but one device remaining: trick his senses into imagining he could still hear the faint chugging of the train in the distance, a repetitious serenade that echoed across a rural nightscape.

*****

The night air did not settle without a nip; only someone who walked from dawn to darkness could shrug it off and sleep. He did not experience, despite nary an expectation of waking in a bed—an awareness that remained uncompromised—a fitful night’s slumber. It was, however, eventful, as Andy’s subconscious invited a parade of incongruous episodes, a stream of unconscious impressions with similar beginnings and different endings.

On a table, in plain view, are lovely, delicate hands; they belong to someone broken and craving love. Darlene? But wait, something is amiss, out of character. The diner is desolate; the unexpected anomaly engenders dismay. Where are the men, those boisterous steel, timber, and coal producers? Andy’s eyes rove a dark room filled with empty chairs and tables, then set them once again upon the hands of the nymphet. Had he, unwittingly, his consciousness in tatters, doubled back to Clintonville? Darlene, you waited for me! The notion of a girl, perhaps a kindred spirit, hastens the essence of joy; thus, hands, once the source of female incursion, are a comfort; he wants to reach for them, touch them, even kiss them, and pray they would lead him past a threshold to a place of peace, where only exquisite sensations may thrive. He allows his eyes to travel the length of Darlene’s arms—so sinuous, so fair. At the end of his traveled gaze, he sees not the face expected but that of a man—a face twisted into hideous distortions, perhaps a malevolent satyr or hellish beast; its vileness frightens Andy. He recoils.

“What’s wrong, Andy?” the creature hisses contemptuously. “You don’t recognize me? Don’t you know who I am?”

Andy shudders at the man’s vileness, the shrillness of his voice.

“I was quite handsome in life, wasn’t I, Andy?” A cautionary tenor resonates; the malevolence in the man’s eyes softens. He pauses and offers a grin, mordantly paradoxical. No sooner than Andy saw past the distortion hell made of the man’s face, his vileness returned with the force of a raging storm at sea. “It’s what we are on the inside that we end up looking like for all eternity. You would be wise to remember that, Andy. Do you hear me? YOU WOULD BE WISE, INDEED!!”

Again, Andy’s gaze is drawn to Darlene’s hands spread prettily atop the table. Wary of allowing his eyes to travel the length of her arms, an impalpable force compels him. Before he could glimpse Darlene, her face had dissolved into a mist. In its wake, he sees a young girl—so delicate, so innocent—carried off by the vile creature. On her face glows an expression of serenity one might wear when insensible to danger or fooled by a trickster or, worse, a fiend. Andy’s heart sinks, realizing the girl’s expression is not one of serenity but resignation, for it is apparent she understands the danger but hasn’t the will to resist and is carried off without a struggle. The fiend glares back at Andy; its laughter is hideous. Andy is desperate to rise, to dash off and rescue the girl, fight for her life, or bargain for her innocence, but he cannot pry himself from his chair. He cries out her name, but one’s own voice cannot travel in dreams.

A third time, Andy takes in the nymphet’s hands. A third time, it is not her face that greets him when he raises his head. Moreover, the scene has altered; he senses a different ether. No longer visible are empty chairs and tables in a dark, lifeless room. Miasma—if he is still within the diner’s walls—impedes the expected, however illusory. The effort of standing springs without awareness, yet he is on his feet. Walled in by mist, he narrows his gaze to penetrate the thickening layer when he spots a shadowy figure in the distance. No discernible traits are apparent on the figure—neither shape nor size—as it advances upon him in wraithlike movements. Andy shudders that the mysterious figure is a phantom or malefactor. He recoils as it emerges through the thickening layer. Its form grows larger and larger, its manifestation increasingly ostensible until she reveals herself a sister attired as one would when belonging to a Catholic order. Serenity is evident in her mien. When their gazes meet, the sister’s lips form the inaudible words, “Thank you.” She nods meekly and, from her knees, presses a cheek to Andy’s hand, then returns to the mist from which she emerged.

“Who are you?” Andy cries. There is no sober reason to suppose the sister traveled years across time to express gratitude, but it is an unquestioned belief that Andy clings to.

The mist dissipates, revealing anomalous desolation. Emboldened, Andy reaches for Darlene. Chosen by an incorporeal authority, she is his gateway to the subconscious universe—a shapeless zone where the past, present, and future converge—and he wishes, through her, to summon the sister, to thrive in her godly presence, to feel through her touch intimations owning capacities to imbue his soul with the malleable nature of mercy. His fingertips contact Darlene. The consequence is a jolt; it sends him spiraling through the universe, time, and eternity and plants his feet in a dewy, shadowy wilderness at the onset of dawn. He is not alone; alongside him stands a child, tiny and frail—an angelic luminosity hides that it has suffered an illness. Andy cannot look upon its face; an imperceptible force, an unknown entity, prevents him. The child takes Andy by the hand and leads him through the wilderness. Piercing the dense ether, they glide above the coolness of the grass, passing that which is familiar: scenes of childhood, the present, and, strangely, the future.

“How do I know these places?” he asks of days yet to come. The child ignores his entreaty. Their journey ends at the bank of a lake. There they stand, Andy and the tiny child, their feet pressing into the cool earth. The child, whom Andy theorizes to be an androgynous dwarf gifted in the art of sorcery—though its mannerisms are strangely familiar—waves a hand and says, “You can see it, can’t you, Andy? That one day, all will be as it should?”

Andy pleads with the child, “But why can’t I see you?”

“One day, you shall.” The child walks away. Andy’s feet remain fixed to the earth; he cannot follow.

“Wait!” he cries. “Where are you going?”

The child turns its gaze upon Andy; its face is but an impression in the misty dawn. It points and vanishes to an unknown dominion.

*****

Andy woke refreshed. The grass alongside Sycamore Road proved sufficient. He went tearing into The Snow Shoe, seeking Regina.

“The world is clearer than ever,” he gushed. “I saw everything; I know what I’m supposed to do. Tell the cook I said ‘thank you’ and that he won’t regret giving me a second chance.”

“I beg your pardon,” Regina intoned. “Do I know you?”

“I…I don’t understand.” Faltering as though the universe reshuffled the deck and all matters misaligned, Andy reached for the door.

“Just a moment,” said Regina. “Are you Andy?”

“You remember!” Andy cried.

“Remember what? I only meant to say someone left this for you.”

Andy regarded the envelope with suspicion. He tore it open and read:

I warned you we’d meet again, soldier. The forsaken children of the world are its true angels. We walk the Earth unheralded, unloved, or worse. We are humanity’s conscience and must bear all human failings. Often, we must bleed so that others can heal. Because of you, Karen survived. Now, it’s time to move on. There is much work to be done.

Andy opened the door just as a man was passing through. “Good morning, Sir,” Regina called to him. “Your kitchen awaits you.” The man turned to Andy and winked. The morning sun illuminated his wavy white hair and beard. Andy let loose the laughter of irony. “Of course it’s you,” he said of the tinkering old man. “Of course, you’re the cook.”

BOOK II

IN SEARCH OF BLUE SKIES

Lock Haven sits between the banks of the Susquehanna River and Bald Eagle Creek. With a downtown featuring Gothic Revival churches, museums, tree-lined streets with quaint shops, lamp posts dotting the sidewalks, horse-drawn carriages touring out-of-towners, and rambling hills bellying through vistas, it’s no wonder it’s dubbed the crown jewel of central Pennsylvania. Andy ducked into The Bald Eagle, an airy and buoyant café featuring terra-cotta floor tile, stucco walls, tapestries, and an artificial waterfall that trickled into a pond containing fish claimed to have been caught from Bald Eagle Creek, though most locals disbelieved the latter and suspected the fish were store-bought.

“My old man’s been fishing Bald Eagle Creek since Eisenhower,” said Phil, a café busboy, to another, Harold. “He never caught anything that looks like what’s floating in this goddamn pond.”

When he saw she had a free moment, Andy approached Molly, the young woman who greeted and seated patrons of The Bald Eagle. “Might I have a word with the manager?” he asked.

“The manager and owner are one in the same,” she said, still winding down from the lunch rush; her moon-shaped face and buoyant curls had yet to settle. “Would you like to speak to the owner?”

Amused, Andy said, “Sure, let’s try the owner.”

“Was everything all right with your meal?” Molly struck a guarded pose—an employee with a vested interest. The Bald Eagle was a family affair, and Molly was unaccustomed to fielding grievances.

“It was superb,” Andy said, hoping to ease Molly’s protective deportment.

“And the service?”

“Stellar. I want to inquire about picking up some work.”

“Oh,” Molly intoned. “Wait here. I’ll fetch my uncle. His name is Mister Schultz.”

Before long, a stout man of imposing width, Andy guessed was Mister Schultz, emerged from the kitchen. He was atypical of a restaurateur; a longshoreman or construction foreman suited his form. Anyone would find his narrow eyes, bulbous nose, and hulking physique menacing, and “anyone” included Andy. Luckily, Wilbur Schultz’s tone and manner lacked accord with his appearance. The owner of The Bald Eagle gestured to an open table. Andy followed.

“Looking for work, if I heard correctly?”

“I am.” Andy felt encouraged. Molly warned her uncle why he was summoned, and instead of returning to shoo Andy away, her uncle made a swift appearance.

Wilbur Schultz acknowledged how capable Andy appeared but could only offer kitchen help, which was a revolving door lately. Andy, sparing no concern of acting over-eager, readily accepted.

“I take it you attend the local university.” The question surprised Andy.

“No, Sir,” he replied, without bothering to explain that he was nearing the end of his freshman year of high school.

The next leap in logic saw Andy as a high schooler looking for part-time work he could parlay into full-time come the summer. Why would Wilbur Schultz assume otherwise? Andy, mindful of sounding assertive but not demanding, said, “If it’s all right with you, Sir, I’d like to start working full-time tomorrow if possible.” Thus came the next logical leap; it placed Andy at the end of a high school career, a commoner of sorts, desperate to scratch out a living regardless of how meager. It marked a head-scratcher for Wilbur Schultz, as Andy, a young man, fit of form, with clear, intelligent eyes, hardly fit the description of a young man down on his luck. Wilbur Schultz’s narrow eyes probed, but all he could infer was that something seemed askew; there was a missing piece to what he alleged was a puzzle sitting across from him. He considered rescinding his offer. Then, the puzzle inquired about a place he could afford on a dishwasher’s salary. No sooner than the utterance settled in Wilbur Schultz’s ear, the missing piece settled into place; it completed the puzzle.

“Christ!” Wilbur Schultz growled, his demeanor shifting to match his form. “You flew the coop!” Thrusting his arms upward, he waved his hands as one tends to when thinking aloud. “Every spring, they come out of the woodwork, these rebels looking for a cause. They stay put through winter, then, no sooner than the snow melts, all their brazenness gushes out.” Looking squarely at Andy, he asked, “Have you ever noticed that?”

“Can’t say that I have.”

“Take my advice, kid; hightail it home,” Wilbur Schultz urged. “Trust me; you’ll thank me one day.”

“If I could do that, Sir, I wouldn’t have come here asking for a job.”

The solemnity in Andy’s tenor disarmed Wilbur Schultz. Still, the Bald Eagle’s proprietor gibed, “Whatcha do, knock up some teenybopper and are running scared-shitless from her crazy old man? Andy frowned. With a wave of resignation, Wilbur Schultz intoned, “Forget about it, kid. If you wanna work my kitchen, be my guest; it’s safer than running away with the circus.”

Wilbur Schultz was not one to delve into a crowded sphere known as the world of troubled teens; what would it cost to give Andy a break? Meanwhile, one who fell from grace would work his fingers raw for low-end wages, a scenario that would chase him back to wherever he had fled.

“They might have a room for you at Blue Skies; it’s a boarding house of sorts.” Andy was sure he saw Wilbur Schultz grimace. “Okay, it’s a halfway house. Margret Cleary—she runs the joint—prefers it not to have the stigma of a house only suitable for those whose lives, for whatever reason, fell into the crapper. I’ve known Margaret Cleary for years and can vouch that Blue Skies is safe and well-run. I’ll put in a word that she should expect you.” Wilbur scratched out directions and barked, “First thing tomorrow morning! Eight o’clock sharp!”

Spring flowers don’t grow from nothing. Andy was not a block from The Bald Eagle when Mother Nature—throughout his travels, she had shown herself cooperative if not merciful—unleashed her fury. Dark clouds chased the sunshine and hastened a shower, followed by a wind-driven downpour. Instead of searching for Blue Skies, Andy sprinted back to Highway 220, where earlier he spotted The Jolly Roger, a roadside inn.

He entered the lobby, winded from sprinting; rainwater dripped from his skin and jacket. Behind the check-in desk sat Wally Frick, a petite man, spectacled, with a miserly endowment of hair, save for the unattended wisps above his ears and nape. Wally Frick had entered his third decade manning the same lobby from the same well-worn chair. A head in a downward tilt with eyes buried in yesterday’s newspaper was the bearing he chose when pretending not to notice Andy’s presence. Feigning ignorance was Wally Frick’s way of punishing Andy for appearing a winded and bedraggled mess dripping rainwater on his carpet. Andy made a coarse throat-clearing noise; it prompted Wally to utter, without sparing an upward glance, “A bit moist out there, I take it?”

“You noticed that too, huh?” Andy’s derision matched Wally Frick’s. Then he asked about a room.

“Sign says vacancy, don’t it?” said Wally Frick, still pinned to yesterday’s newspaper.

Andy wanted out of his wet clothes, and all that stood between him and a hot shower was a dismissive little man more interested in testing patience than renting rooms. Andy placed the palms firmly on Wally Frick’s desk, puffed out his chest, and uttered decisively, “I’ll take a room.”

“Be twenty-five bucks,” said Wally Frick. He adjusted his spectacles further down the bridge of his nose and shifted his eyes upward, taking in the peculiar array of features that made up the face of our traveler. It was not a courtesy; Wally Frick was curious to see how Andy would react to the cost of a room.

Andy separated twenty-five dollars from a wad of soaking-wet bills. The arithmetic was troubling, but he had procured a way of replenishing his till. He peeled his gaze from Wally Frick to a wind-driven downpour that showed no signs of waning and weighed the value of not having to slumber in cool, wet grass. He slapped the cash on the desk. Frowning as though he had every expectation the cost of a room would chase Andy back into the rain, Wally Frick reached for a key. Before handing it over, he said, “A driver’s license?”

Andy’s torso deflated. Why a driver’s license? A twinge of panic that the world was more daunting than expected surged. Feebly, he reached into his back pocket for an item he knew wasn’t there.

From a puffed-out chest to the innocence of boyhood, the pendulum had swung. Again, Andy glanced at the wind-driven downpour. Resetting his eyes on Wally Frick—it was now Wally displaying a loss of patience—he asked, “Why a driver’s license?”

“Motel policy. We like to know that folks are who they say they are. In the event you’re a fugitive from justice, and the police come snooping around, we wanna do our part.” Smugly, Wally Frick added, “Call it community service.”

Andy explained, “I just arrived in town this afternoon… on foot. I start work tomorrow at The Bald Eagle. You can call and ask Mister Schultz; he’ll vouch for me.”

“Working for ol’ Shultzie, are you? Nice place, The Bald Eagle.” Wally Frick handed over the keys as Andy signed for the room. “But don’t think I won’t call over there ‘cause I will. You see, we roadside motels get all types: cheatin’ husbands and wives, wayward women, men peddlin’ all sorts of material the law don’t find favor with; every other person that walks through that door is either a John or a Jane Doe.” With a scornful chortle, Wally Frick added, “If they only knew,” then tapped his head to advise he was the owner of a mind from which nothing escapes. “I have to give you credit, kiddo; Andy Truman is original.”

“It’s Trumaine.” With key in hand, Andy felt empowered to rebuke Wally Frick for mispronouncing his name—it was a purposeful misspeak—and reveal a demeanor of disdain for whatever qualms the little man harbored concerning Andy’s character.

“Truman, Trumaine, have it your way,” Wally Frick intoned. “I can usually tell when folks have something to hide, and when a fella your age comes passing through all by his lonesome wanting a room, a salty old sonofagun like me gets to wondering, what’s he running from? Who’s looking for ‘im? But, as you claim, you’re workin’ for Shultzie. We shall see.”

Andy turns a key. Inside, he steps, sheltered from the rain, the adventurous road, and the darkness of night. He peels off his wet clothes and drapes them over the baseboard heater, which he cranks to a toasty temperature. Huck Finn remains in good condition despite his backpack soaking up its share of rain. He lays both items, along with his wet bills, on a nightstand, then indulges in a shower until the water turns tepid. He lies down his lengthy nakedness, surprisingly weighty and justifiably lifeless, atop a typically uncomfortable motel mattress. He regards himself as a mid-teen might, but the predilection for onanism eludes him. Numb from weariness—his ears experience the peculiar whir absolute silence tends to create—he remains motionless, pondering solitude and aloneness. They lack kinship, diverging beyond the realm of corporeality: solitude is a choice, a sabbatical from people; aloneness is a state of mind, a wretched disposition of being. Bright and early, he will return to The Bald Eagle. It has only been days—days walking, encountering an old man and nymph… or were they angels?—yet it seems an eternity since last he made a return trip to a familiar place.

Next, he glances over his shoulder at the other nightstand, flanking the bed. Atop sits a telephone. While journeying, Andy experienced nary an impulse to call the place he once called home. Yet, there he lay, alone at a roadside inn—a youth desperate to keep a weighty past from colliding with the present while grasping an uncertain future whose olive branch is an ambiguous message delivered to him by a ghostly dwarf in a dream—longing to hear a particular voice. Did he yearn for a voice, or was it availability stoking his desire? He considers ripping the jack from the wall and, to quell further temptation, tossing the phone into the parking lot. Turning to regard the bills laid to dry atop the opposite nightstand, it finally occurs to Andy that Wilbur Schultz became so distracted guessing his predicament, and he, in turn, got drawn into Wilbur Schultz’s distraction, the matter of an hourly wage never made it into the discussion. Again, he regards the intact phone; it remains the object of a pensive gaze. He reaches for the receiver and withdraws as if clutching it would prove an act carrying irreversible consequences. He begins wearing out the carpet, agonizing over what to say—depending upon who answers—should he overcome his misgivings. Finally, he grips the receiver and presses it to his ear, but his mouth turns to dust no sooner than his finger comes one number shy of completing the familiar sequence. He sidles into the bathroom for water. Upon returning, he recognizes the sweet resonance drifting in from the west; it gently fills his ear like a lullaby.

My God, Karen, what have we done? Will God forgive us? In that ambiguous place we call a soul, will we ever see a day when we can close our eyes and know it was all worthwhile?

Andy wants to say all that and more but fails to utter a word. He remains quiet as the loveliness at the other end, three times, beckons the caller. Andy hears a click as Karen Trumaine settles the receiver into its cradle. Andy crawls back into bed. His body is weary; his emotions reduce him to tatters. Karen prevails as an albatross until Andy succumbs to exhaustion.

*****

Andy strolls into The Bald Eagle at 7:45. His employer, accustomed to younger staff members showing up in the nick of time or a few ticks tardy, greets him pleasantly. Wilbur Schultz escorts Andy to the kitchen and explains his duties. “She ain’t glamorous, kiddo,” and gives Andy a healthy swat on the back.

It was not glamorous; kitchens rarely are, but for a young man who, as Wilbur Schultz put it, flew the coop, the area at The Bald Eagle where food got cooked, dishes clanked, and steel pots rattled against steel countertops, creating a strident din, represented a refuge.

“Let me introduce you to Doc, our master chef,” said Wilbur. Wilbur gestured for Andy to stoop so that he could whisper in his ear. “I must warn you: Doc’s a man of few words and sometimes doesn’t talk. You’ll have to anticipate his needs. Good luck.”

Doc acknowledged Andy with a begrudging nod.

“Gotcha a new assistant, Doc,” Wilbur announced brightly. “A terrific kid, this time.”

Without diverting his eyes from the stove, Doc muttered, “Swell.”

“See what I mean,” Wilbur whispered to Andy before lilting away, leaving Andy alone with the master chef.

Andy was not unfamiliar with intense-looking men—Jack Squirek, his running coach, among them—but didn’t understand intensity until today. More than Doc personifying intensity, he was alleged as too frightening to be alone with. He stood six feet plus inches and was two hundred pounds of scowl—a medieval executioner in Jimmy Carter’s America—a feudal warlord in a postwar society. And those eyebrows! Dark, bushy, and intimidating—menacing features accenting a frightening face. Andy couldn’t help staring; to not regard Doc’s brows was akin to feigning ignorance of a glaring deformity or multicar pileup.

Doc’s instructions, as Wilbur warned, came in the form of a word, if not a grunt, mimicking the distress of constipation. When Andy heard “broom” growled, it was time for a clean-up; Doc did not care to listen to his shoes crunching dropped food. Mop was growled in frustration; it annoyed Doc when an assistant required enlightening to liquid on the floor. The hand instruction echoed in a raised voice, which meant Andy had better drop whatever he was doing and assist. Pot meant not material to tamp in a bowl but step on it with the washing; I don’t have all day! The latter prompted Andy to attack pieces of cookware, similar to a katydid rubbing its wings. The only time Doc bothered to form what qualified as a sentence was when he needed something from the walk-in fridge; he didn’t want the newbie squandering half the day searching for food. Less than whimsically, Andy entertained the notion that below The Bald Eagle was a dungeon imprisoning Doc’s former assistants, suffering the vilest deprivations while awaiting their date with the executioner’s axe.

After the lunch rush, Wilbur Schultz sauntered to the kitchen, over to Doc, and asked, “How’s it going?”

Doc growled, “No complaints.”

Paradoxically, Wilbur crooned to Molly after he and his stoutness went lilting from the kitchen, “Doc just made a goddamn speech; the kid must be a natural!”

Indeed, Doc was a man of few words. Like some who work with their hands, he saw no need to chatter unnecessarily. Doc’s opinion was that most chatter, be it the weather or about a ballgame—matters of frivolity and fad—was unnecessary. Wilbur Schultz, who played fullback for the Division II Kutztown University Golden Bears, yammered to Doc about his alma mater and Joe Paterno’s higher-profile Nittany Lions. In every instance, he failed to lure Doc into a conversation. From the moment he donned his apron until he took it off, Doc personified concentration, which others interpreted as a permanent scowl. A true culinary artist, Doc had an artist’s temperament—a nature many find overbearing. Only Wilbur Schultz knew Doc beyond the walls of The Bald Eagle. Wilbur had gotten wind of a chef making a name for himself in Williamsport and managed to lure him to Lock Haven, or so the story goes.

Come day’s end, Andy knew better than to wait to hear Way to go, kid, or Good first day; I hope you last longer than my last three assistants below awaiting execution.

“Goodnight, Doc,” said Andy.

Doc made a throaty sound resembling a word. Nevertheless, Andy sensed Doc liked him, though a favorable opinion would not take the sting out of what a day’s worth of dish detergent and water did to his hands. He was on his way to Blue Skies and a date with Margret Cleary.

*****

The structure currently carrying the name Blue Skies began as a residence built in the late 1840s. It saw multiple iterations, including an army hospital during the Civil War, before becoming the Cleary homestead, over which Margret was the last to preside after caring for an alcoholic father wasting away with cancer.

Andy rang the doorbell and struck a humble pose on the grand veranda of Blue Skies. No one attended his beckoning. He rang a second time to the same result and assumed the bell no longer functioned. Taking the lion’s head knocker in his hand, he pounded it against a steel plate fastened to a stout door. Before long, a tall, slim woman with graying hair pulled severely off her face and gathered into a tidy bun had appeared. Her plain charcoal-colored dress, which supplied an adequate backdrop for her heirloom pearls, revealed a swanlike neck and delicate wrists and stopped at the tops of her black shoes. She seemed well in accordance with Blue Skies; anyone might guess she was a curator of a home whose historicity lured tourists.

“You must be Andy Trumaine.” A voice smooth as satin settled in Andy’s ears; it was as cozy as burning wood on a winter’s night. “I’m Margret Cleary. Wilbur said I should expect you.” Her mien twisted when adding, “ But that was yesterday.”

“I had some difficulty with the weather,” Andy confessed. “I appreciate you letting me stay at Blue Skies, Missus Cleary, despite being a day late.”

“A day late or a week; I’m not letting you do anything.” Margaret Cleary’s words carried a surprising snap. Andy’s head, which he bowed respectfully, jerked upward; his eyes widened. “You’ll be paying your share, just like everyone else. And it’s Miss Cleary, thank you very much.”

Andy stepped back, fearful that Margret Cleary had a concealed weapon on her person and was prepared to brandish it liberally. He dared an upward glance and saw a smile form on Margret Cleary’s face. He knew at once the steward of Blue Skies was having fun with him. “Come in, Andy. I’ll give you the grand tour.” Margret Cleary placed a long, slender, reassuring hand on Andy’s shoulder. Her charcoal housedress remained undisturbed as she ambled in and out of many rooms with decorous posture and poise.

“We don’t keep a long list of rules at Blue Skies, but those kept are abided by unwaveringly: Breakfast is at 6:30, dinner at 6:30, and the front door is locked at ten-thirty p.m. sharp. There are no exceptions to the latter. We don’t tolerate any late-night carousing. Also, we pray.”

Margaret Cleary’s affecting use of the word “we” amused Andy. “Over the years, we have had all sorts: recovering addicts and alcoholics, men who have gambled away everything but the shirts on their backs; those who wash up on our shore have lost all they had to lose, save for their souls, and some came dangerously close. But, through structure, working an honest job for a fair wage, and surrendering to a higher power, bit by bit, they can piece back together their lives. Everyone here was once young and filled with hopes and dreams. Unfortunately, life, if we allow it, and sometimes even if we’re on our guard, has a knack for kicking us to the curb, and often, those who get kicked find ways to punish themselves. But there’s always hope on the horizon—or, as we say around here, ‘Blue Skies.’”

Margaret paused to allow Andy to ponder the essence of the haven she created.

“I don’t mind admitting I was skeptical; I don’t usually take in itinerants, especially youths. But since Wilbur vouched for you, and I had a free room…” Andy shrugged as one would when promising their presence would not prove a nuisance.

“One more thing, Andy.” Margret Cleary abandoned her satiny-smooth wood-burning tone for sternness. “At Blue Skies, we respect one another’s property and privacy, and regardless of what brought us here, our core principle is that we are all equal in God’s eyes. Now wait here; I shall not be too long.”

Margret Cleary disappeared, leaving Andy alone in a sitting room featuring walnut panels, brocade fabrics, and a bookshelf built into a wall comprised of Twain, Faulkner, London, Dickinson, Steinbeck, and Hemingway volumes. Andy scanned the opuses, including the spots where he deduced White Fang and Of Mice and Men were missing, then grew distracted by the clanking of eating utensils against plates. He heard no exchange of words, which could indicate superb food or lousy company; Andy prayed for the former. Margret Cleary returned with a bathrobe. Andy followed her to the cellar. “I’m guessing your clothes haven’t been laundered for a spell, discounting the rain.” A sheepish grin came over Andy. “Foolishness gets around,” he said.

“Our less redeeming aspects have a knack,” Margret Cleary added paradoxically. “But we needn’t dwell on that. I’m much more interested in hearing how you like working for Wilbur?”

“It’s fine,” Andy replied. He wanted to say more, but what could he add to a day in the life of a kitchen lackey? Finally, it occurred to him, “Mister Schultz said you and he have known one another for years.”

“He didn’t happen to mention how many years?” Margret Cleary paused long enough for Andy to reply but received an ineffectual shrug. A thoughtful look came over her—her bearing softened to a state of wistful ambiguity, akin to one preparing to ponder a regretful past. “Wilbur took a shine to me our senior year of high school, and I didn’t mind the attention. He asked me to the prom, and I didn’t hesitate. Wilbur was handsome in a rugged way. He played football; he might’ve told you. Father didn’t care for football or men of brawn; he was urbane; he enjoyed peaceful pursuits. Come the evening, Father would read and play the violin. He played well and favored Schuman; Scenes from Childhood was his favorite. Father sneered whenever Wilbur called on me, and, in those days, I wasn’t a strong enough girl to be at odds with her father. School ended. Wilbur went off to play football at Kutztown. I felt abandoned and grew to resent Father; it led to making rash and immature decisions, like running off with Kenneth Harrington. Kenneth had big dreams and the ambition to pursue them. I let him sweep me off my feet and carry me to Pittsburgh, where he fulfilled his dream of becoming an architect. Then Kenneth, as it has been known to happen in marriages, grew bored. Well, anyway, I suppose that’s the way it goes. And now I’ve returned to the home of my childhood.”

Margret Cleary paused. She felt strangely unburdened. “I never told that story to anyone,” she said. “I can’t say why I felt compelled to tell you, but I’m glad I did.” She continued gushing to her youthful confessor until her voice faded into silence, her gaze distant, her thoughts far away, or perhaps as nearby as an across-town café. Shedding her wistfulness, Margret Cleary told Andy, “Just this once, I’ll launder your clothes. They’ll be placed outside your room, which is up the main staircase to your right, the second-to-last door. For now, use this robe.”

Our traveler crept to his room, placed Huck Finn in a nightstand drawer, and collapsed in bed. As he had when pressed into the tall grass alongside Sycamore Road, he listened to the faint chugging of a distant train, a mechanical symphony echoing in the night. And then his lids drooped shut. Come morning, he delighted in the sun’s early rays, imagining himself a flower compelled by their properties or any entity owning the capacity to harness energy. Not until his cloudy head raised from his pillow and he rubbed the sleep from his eyes did he remember Margret Cleary’s 6:30 a.m. breakfast rule. What impression would it make on his cohabitants if the newbie, a boy in a man’s world—doubtless that latter would be the perception—screwed up his first Blue Skies breakfast? He launched his lithe and lengthy form from a forgiving mattress, jumped into the clothes awaiting him outside his door, and tore down the hall. Upon hearing the squeaking his feet produced on the 130-year-old floorboards, he stopped and cringed that his brief stampede incited numerous scowls below.

Blue Skies is a living, breathing piece of history. With each footfall, its pre-Civil War construction, aside from reminding its inhabitants of a bygone era, tends to talk back, sometimes loudly. And despite its limited vocabulary, it’s a house with a lot to say: every corner and nook, ornate moldings, panels, and fixtures, tell a story that marks an era. To live at Blue Skies is to brush up against history; one could sense the spirit of antiquity when placing a foot on its grand veranda.

When tiptoeing on the staircase, sunlight breaking through a round window above the front door blinded Andy. Fearful he was tardy or cut it too close, he scampered as lightly as his feet allowed toward the kitchen where Margret Cleary and his ten co-habitants had already gathered. His throat constricted when upon him set, in unison, ten sets of eyes; Margret Cleary had yet to look his way. Were these men not made aware that among them dwelt a boy—Daniel in the lion’s den? Eyes were bearing in on him from every angle, forcing his gaze upward, thus allowing him to locate a clock high on a wall that announced he had minutes to spare. The penetrating eyes of these men on the mend were not the result of Andy’s tardiness but curiosity: The newbie did not appear broken, just out of place.

Andy assessed himself as the youngest occupant at Blue Skies by a wide margin—a man-child among a crew of salty old veterans. The range in age began with Joe Duffy, twenty-four, and ended with Corky Grimes, sixty-one. Everyone stopped whatever it was they were doing to greet the newbie, who observed breakfast as a community affair: One made coffee, another toast, one flipped omelets, another fried bacon, another squeezed orange juice, and all the while, George Peckinpaugh grumbled when reading aloud each item in the newspaper. George Peckinpaugh, generally, groused and bellyached and, upon scouring the newspaper, was given to opine that President Carter was “In over his head” and that “Not for a stale cigarette butt should we trust those goddamn Ruskies.” News of any kind failed to please George, but he delighted in the notion that he was enlightening his brethren. “If we have to be a bunch of also-rans with ex-wives and estranged kids, we might as well know a thing or two about the crumby world into which we’re about to reestablish ourselves, goddamnit!” That would more or less sum up the philosophy to which George Peckinpaugh subscribed.

Blue Skies comported itself as a collective; one might mistake it for a bed-and-breakfast where old friends staged reunions. Despite their fall from grace, thanks to Margret Cleary, no one felt ashamed to be there or that Blue Skies had become a necessary stage in their life. Ten men offered Andy a welcoming hand and showed him a place at the table. Like Margret Cleary, Corky Grimes detected something luminous in Andy’s mien.

Using the cheeriest tenor he could summon, Andy strolled into The Bald Eagle’s kitchen and crooned, “Mornin’, Doc. How are you feeling on this finest of Thursdays?” Doc raised an imposing brow. Little else other than What the hell is so special about this or any Thursday one might infer from his tacit reciprocation.

And thus began a routine Andy imposed on Doc: cheery greetings in the morning, good nights in the evening, and, when an opportunity presented, inflated pleasantries during the day. But Andy never could goad Doc to sidle from the temperament that personified the culinary artist. Moreover, Andy could intuit where the imaginary line known as too far was drawn and did not dare cross it.

If truth be told, Doc liked Andy. Besides, what were the prospects of shaking a tree and having a cluster of non-complaining teenagers fall out, lining up to work as his kitchen lackey? “Trust me,” Wilbur Schultz told Andy, “if Doc didn’t like you, you’d know it; there’d be no need for guessing. Just last summer, Doc damn near decapitated a dishwasher when he heaved a pan across the kitchen. Petey Kostmayer was the poor bastard’s name. No one has seen hide or hair of him since.” Dropping his anecdotal tone, Wilbur added, “For Doc, food is like religion and just as sacred—like when Jesus broke bread with the apostles. For Doc, every meal is the last supper. Moreover, the sonofagun could turn paint chips and toaster crumbs into something to make your eyes roll in their sockets.”

Andy phoned Margret Cleary to tell her not to save a place at the table, that he would fill his belly at The Bald Eagle. He hopped onto the grand veranda and noticed Corky Grimes’s nose buried in Of Mice and Men. The mystery was solved. Although the case of the missing novel from the Blue Skies library was not much of a mystery: Corky Grimes, with his well-weathered façade, more miles behind him than in front, and eyes brimming with wisdom and tragedy, could have walked out of the pages of any number of Steinbeck opuses. Andy read Of Mice and Men over a snowy weekend in February. The sky had darkened. With only a dim porch light, it became too difficult for Corky Grimes to take in words on a page. As Corky uncoiled his legs and uprighted himself, Andy asked, “How’s it going so far?” After a day with Doc, he craved conversation, be it frivolous or poignant.

“Oh, it’s going.” The consternation in Corky’s strained eyes brightened over Andy’s interest. Andy adjusted his posture to square himself to Corky; he hoped it would encourage the Blue Skies elder to engage him. “Where are you in the story?” he asked.

“Just finished the part where Curly beat on poor Lennie. Lennie held back as long as he could, then George let ‘im react. ‘Get ‘im, Lennie,’ George told him. Lennie caught Curly’s fist and squeezed ‘til it crushed. And I was damn glad he did it; I don’t like that sonofabitchin’ Curly.”

“I didn’t care for him either.”

“And I sure as hell didn’t care for Carlson putting down Candy’s dog,” Corky added. “And don’t take this the wrong way, being that you’re so young, but there’re plenty of folks I’d sooner see put down than a helpless animal. Doing in a loyal old dog just ‘cause it isn’t as useful as it once was doesn’t set right with me.”

Andy winced. Corky Grimes’s brand of justice concerning old dogs and plenty of folks did not ring unfamiliar. With Andy’s shift in demeanor, Corky excused himself for the parlor. When going for the door, Andy noticed Corky’s limp and figured it was only natural an aging man, down on his luck, would feel more sensitivity than most for an old dog euthanized.

In a quiet parlor, Andy learned how a boy, from age eleven, steered logs down the Monongahela River. The year was 1927: Charles Lindbergh, in The Spirit of St. Louis, completed the world’s first transatlantic flight and, in doing so, taught a youth how to reach, hope, and imagine. But steel and timber are magnets for men of the Rust Belt. Eventually, Corky Grimes would see a reprieve, but not a welcome one: a tour of duty in the Pacific theater of the world’s most epic war could make anyone wish for a life of steering logs down a river. Beyond learning to hold, clean, and shoot a Springfield and Thompson, the Army taught Corky to drink. Back on the river, steering logs, he fell through but had the presence of mind not to try to surface. Instead, he swam underwater and clutched a protruding tree root on the bank, narrowly avoiding the tons of lumber floating past. Like any fool not wishing to divorce himself from a vice, Corky credited not the cold water for instantly sobering him into making a swift decision that saved his life but the all too accessible moonshine he alleged to have boosted his bravery.

His marriage began its steady erosion when the kids arrived, and wages got squandered on whiskey instead of decent shoes. With Elizabeth still a viable woman and his daughters nearly grown, Corky got thrown from a skidder, an accident that left his leg crushed, the damage permanent. Bouncing from one dead-end job to another, he coped with his pain and loneliness by reaching the bottom of more bottles than he could count. Finally, through the tool of faith, he learned perseverance. He parted company with what the Army taught him and what he perfected. The pain endures. Oftentimes, it’s persistent, if not intractable, and always a reminder. Sadly, the world hasn’t much use for an old logger with one good leg.

“Strange,” said Corky, “but since you arrived, I no longer sense defeat and that my sins are no worse than any other man’s.”

Andy was about to drift off when jarred by coughing and hacking that echoed from across the hall and moaning and retching next door. He was unsure of the arrangements, nor was he familiar enough with his cohabitants to assign the awful sounds to a given resident, not that he agonized over the matter; it was the price for coexisting with grown men who know a thing or two of sickness, withdrawal, and the long-range effects of warring against one’s body. He lay awake, wondering whether these bellowing bodily disturbances revulsed the willowy Margret Cleary. He went to the window and gazed at a streetlamp, throwing its light upon the glossy blackness of the road. The charm of evening juxtaposed with the sounds of broken men on the mend notwithstanding, he was grateful for the side of the glass he presently occupied.

*****

“I still say those goddamn fish are store-bought and not Bald Eagle Creek fish,” Phil groused to Harold.

“It’s killing you, isn’t it?” Harold never passed up an opportunity to mock Phil’s pet peeves. “49 U.S. Marines died in Barcelona, Communism is rooting in Spain, the Vietnamese can’t stay out of war, it cost us a king’s ransom to discover there’re rings around Uranus, and you reserve your vituperation for Schultzy’s fish! Let it go, for Chrissake!”

“Vituperation? Whudda you do, sit up all night reading the dictionary? And just for the record, there’re no rings around my anus.”

Harold and Phil recently turned sixteen and were nearing the end of their sophomore year of high school. Last summer, they started busing tables at The Bald Eagle. “We’re a tandem,” they told Wilbur Schultz. Amused by their it’s-either-both-of-us-or-neither-of-us tactic, Wilbur Schultz, store-bought fish and all, hired the “tandem.” Despite being opposites in most ways, they worked in tandem since early childhood. Good looks aside, Harold, with wit and charm, could manipulate the shirt off your back in January. Phil, conversely, was a strapping kid able to swat a hardball a country mile and shake off tacklers as though they were no more bothersome than a cluster of gnats. They could sum up their social contract using the five simple words: I got your back, buddy.

Harold’s father stocked a corner of the garage with cases of Pabst Blue Ribbon. He would grab and chill a few cans, ensuring they were ready when Joe Paterno’s Nittany Lions kicked off. Harold developed a custom all his own: it involved pilfering quantities his father wouldn’t notice missing. He would stash the thievery in his backpack. When enough had accumulated, come a given Friday, Harold would store his pack in the Bald Eagle’s walk-in fridge. At the end of their shift, he and Phil, cold cans in a sack, would head over to Triangle Park for what they dubbed A celebration of life.

The two had taken a shine to Andy and occasionally sauntered to the kitchen to check whether Doc had Andy’s severed head mounted on a spike. Harold and Phil were also curious about Lock Haven’s newbie, who seemingly dropped in from nowhere and comported himself in a manner ostensibly not of their world. Upon arriving at Triangle Park, Phil, predictably, intoned, “What could be better than Friday night and cold beer?”

“Saturday night and cold beer? But that’s just a crude guess on my part.” Harold turned toward Andy and mimed the hardy-fucking-har Phil never failed to bellow when reacting to Harold’s sarcasm.

“And now, ladies,” Phil grandly intoned, “I shall offer a reply to my own question, thank you very much: For three maidens helpless to resist our charms—especially the charms of yours truly—to appear and offer us their bounty upon which to gorge. That, my compadres, is what could be better.” Inverting his chilled can, Phil emptied a liberal portion into his mouth and then treated the air to a wet, throaty aspiration.

“He’s a real charmer,” Harold told Andy. “The personification of gravity for every unsuspecting postpubescent vagina this side of the Nittany Valley.”

“A guy can be hopeful, can’t he?” Phil whined. “What’s life without hope?”